Is a No-Buy That Bad?

The impossible rules of being a woman: Buy too much, buy too little, get it wrong either way

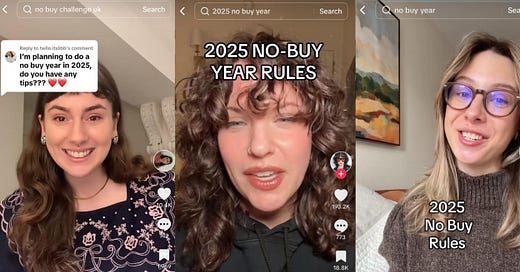

The new year always brings its rituals of restraint. No-buy. Low-buy. Dry January. The shedding of last year’s indulgences, a quiet reckoning with excess. And, as always, the backlash follows. Not just from those who choose differently, but from those who question the impulse entirely.

Why deny yourself? Why shrink your life? Why let scarcity become an aesthetic? Why hand yourself over to a culture that has always asked women to shrink?

I understand the hesitation. I know these questions. I have asked them myself.

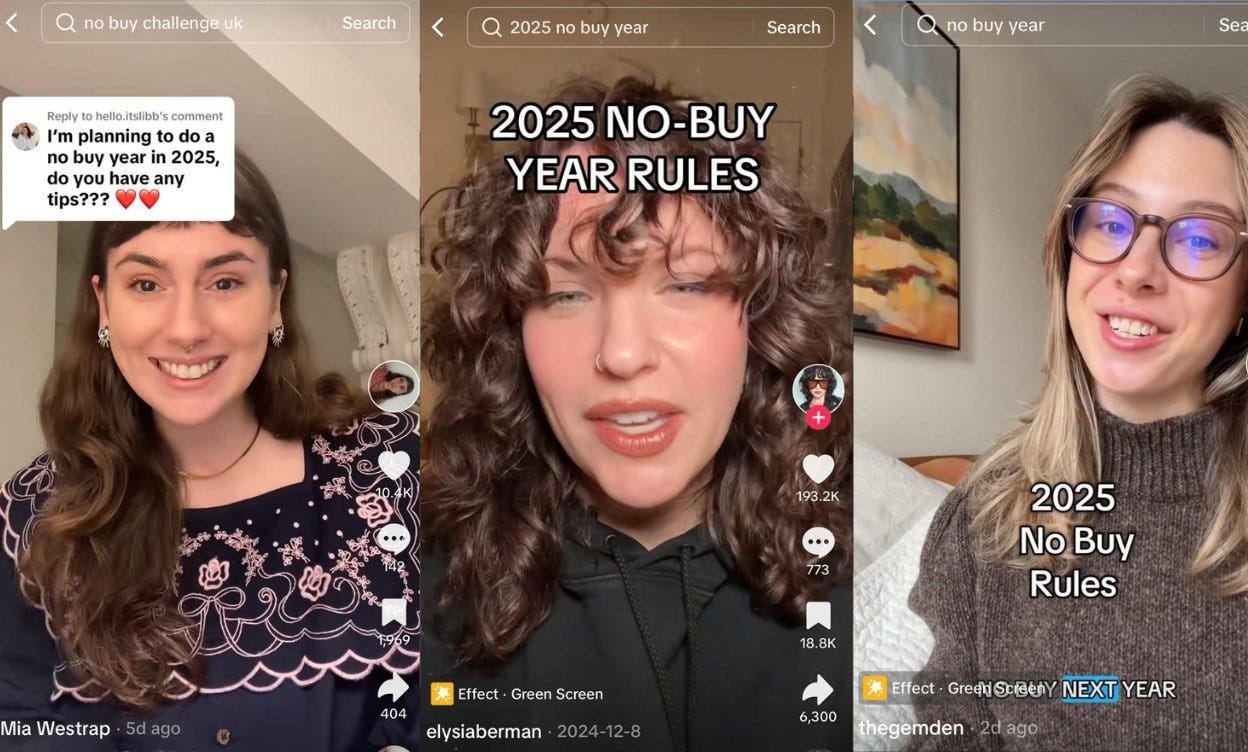

There’s a long, bitter history of deprivation being sold to women as virtue. Smaller bodies, smaller wardrobes, smaller appetites, smaller needs. We have been taught that goodness lies in taking up less space. And yet, something about these conversations feels incomplete—flattened by the assumption that every act of restraint is an act of self-erasure.

But what if restraint isn’t always about self-denial? What if, sometimes, it’s an act of care? If someone has spent years buying things impulsively to fill a void, is it wrong to step back and reconsider? If a person living on a steady diet of fast food decides to cook more meals at home, is that deprivation—or self-care?

I say this as someone in the middle of a low-buy year myself. Not as punishment, not as penance, but as a way to listen more closely to my own desires. To notice where the wanting begins, what fuels it, what quiets it.

Too easily we lose the nuance. There is no denying that diet culture—and, by extension, other forms of self-denial—has been weaponized against women to make us feel small and unworthy. But it is also possible to step back from excess from a place of self-respect rather than shame. *t isn’t always about submission. It can also be about agency. It can be about saying, I have enough—and actually meaning it.

The Distance Between Difference and Judgment

What feels heartbreaking to me is how much energy we spend policing each other’s choices—how easily we reduce, how decisively we turn assumptions into certainty.

A woman decides to buy less, and suddenly she’s punishing herself, starving herself of joy, naively falling prey to a culture that tells women to disappear.

Another woman buys something expensive and beautiful, and now she’s frivolous, materialistic, complicit in the excess of it all.

Why is it so hard to believe that both can be true? That neither is wrong? That one woman’s low-buy can be an act of care, not deprivation? That another can revel in abundance without losing her depth?

Somewhere along the way, we were taught that there is a correct way to be a woman. Not just in how we dress or how we speak, but in how we consume. Buy too much, and you are vain, irresponsible. Buy too little, and you are joyless, performative. Either way, you are scrutinized. Either way, you are doing it wrong.

But we don’t always know what’s behind someone’s choices. We see only the surface—a cart full of purchases, an empty one. We don’t see the quiet calculations, the private reckonings. The woman who shops to remind herself that she is worthy of beauty after years of being told she is not. The woman who stops shopping because she is tired of searching for self-worth in the checkout line.

Both are real. Both are valid.

Recognizing That Choice Isn’t Just Personal

Classical liberalism is built on the foundation of individual autonomy—the idea that people should have the freedom to make their own choices, free from coercion or unnecessary interference. But it also recognizes that freedom comes with responsibility. Your right to swing your fist ends where another person’s nose begins. Personal choice is foundational to classical liberalism, but freedom doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it exists within a shared social fabric. Our choices, no matter how personal, do not unfold in isolation.

Consumption, beauty standards, even the way we discuss restraint or indulgence—all of these choices ripple outward. They are shaped by, and in turn shape, the world around us.

You can respect someone’s autonomy while still grappling with the harm their choices might sustain. A woman who embraces luxury fashion has every right to do so, but it’s worth asking: what does it mean when an industry thrives on exploitative labor? Another woman may genuinely enjoy weight loss as a form of self-care, but when that choice reinforces the idea that thinness equals worth—or worse, when she begins insisting her young daughter follow suit—does her autonomy outweigh her harm to others?

Respecting choice doesn’t mean abandoning critique. It means engaging with complexity. Classical liberalism doesn’t ask us to unconditionally approve of every choice. It demands that we hold both truths: that individuals have the right to choose, but those choices exist in a broader ethical and social framework. Respecting autonomy doesn’t mean staying silent when someone’s choices uphold harm. Freedom isn’t just about the right to choose—it’s also about understanding the impact those choices have on others.

And critique, if it is to matter, must begin with understanding. Haranguing someone, reducing them to caricatures, or making inaccurate assumptions rarely works to change minds. No one has ever been shamed into real transformation.

Understanding doesn’t mean agreement, but it does mean listening. It means seeking to understand not just what a choice is but why it was made. Only then can we hope to meaningfully engage with one another—and the systems in which those choices are entangled.

The Freedom to Choose, the Responsibility to See

Imagine how much kinder the world could be if we met each other with curiosity instead of judgement. If we asked, What does this choice mean to you? instead of assuming we already know. If we recognized that a life well lived does not have to look the same for everyone.

Wat if we trusted that women know their own minds? Or at least, sought first to understand, instead of rushing to judgment?

Empowering women means respecting their agency—their right to choose, free from expectation or justification. To wear makeup or not. To shop or not. To work or stay home. To be slim or fat. To marry or stay single. To have children or not. You can advocate for your own perspective without reducing someone else’s. You can believe deeply in your own choices without needing every other woman to make the same ones. Respecting women doesn’t mean only respecting them when their choices align with your own.

At the end of the day, isn’t that what we all want? A world where women don’t have to prove their worth—through deprivation, through consumption, through anything at all. A world where we can simply choose, without justification, without fear of judgment.

The real luxury isn’t in what we own or abstain from. It’s in knowing that the choice is ours to make—and in making those choices with intention, not just for ourselves, but for the world we help create.

I’ve appreciated so many writers’ thoughtful takes on this! Some of my favorites—I may not agree with all of them, but I appreciate how they’ve made me think:

You may be reading this and thinking, “Um, so you added a bunch of things, but didn’t you just say you still don’t feel like you need anything?”

Yes, I did, and what I said is true. I haven’t set out to buy anything for myself because I genuinely believe I don’t need anything. I source for clients and readers, but I don’t have wishlists or alerts, I rarely scroll and I don’t have Have To Have feelings.

At the same time, I don’t have the same degree of aggro towards buying for myself as I did in June. If in the course of working, I happened upon something that I loved, I bought it. I don’t feel shame or that I’m a hypocrite, nor do I feel the need to dissect these purchases because I don’t feel any internal conflict about them. I simply recognize this as a change in the normal course.

No more numbers, no more nos. My new rule? There are no rules. Entering my Lawless Shopping Era. (Plus: how to know if you want something, key takeaways from 2024, and a go-forward plan.)

Ultimately, style is about curating, not accumulating. It’s about finding the pieces that speak to who you are—not the trends that are trying to sell you a new version of yourself every season. When you embrace this mindset, you begin to develop a sense of style that’s authentic, timeless, and truly yours.

So well observed and heartfelt :) The internet tends to favour polarising opinions and it’s really hard to hold on to nuance when we’re constantly presented with the most extreme versions of any given situation. It’s like we’re so afraid of getting it wrong that we have to double down on a position, when there’s no need to in the first place.

Wow! This was great. I’ve been writing something about my own low-buy goals for this year and this was so reassuring - feeling okay about setting constraints for myself without feeling like I’m giving in to diet/restrictive culture (or perpetuating it!)